With recent extreme weather events in Texas, some are questioning the reliability of alternate energy while others are questioning traditional oil and gas sources of energy. What seems clear is a growing need to have diverse sources of energy, one of which includes offshore wind energy. This is an important topic for many federal agencies in coastal areas that might be affected by these facilities. The following summarizes the current status of wind energy generation, current U.S. projects, and how the regulatory process works in developing an offshore wind energy facility.

What is the History and Current Status of Wind Energy Generation?

The land-based generation of energy from the wind dates back at least two thousand years, primarily as a means to grind grain, ventilate buildings or move water.

Offshore wind farms have many of the same advantages as land-based wind farms. They:

- provide renewable energy;

- do not consume water;

- provide a domestic energy source;

- create jobs; and

- do not emit environmental pollutants or greenhouse gases.1

However, questions remain as to their impacts on birds, migratory fish, and marine mammals. Also, offshore wind farms built within view of the coastline may be unpopular among local residents

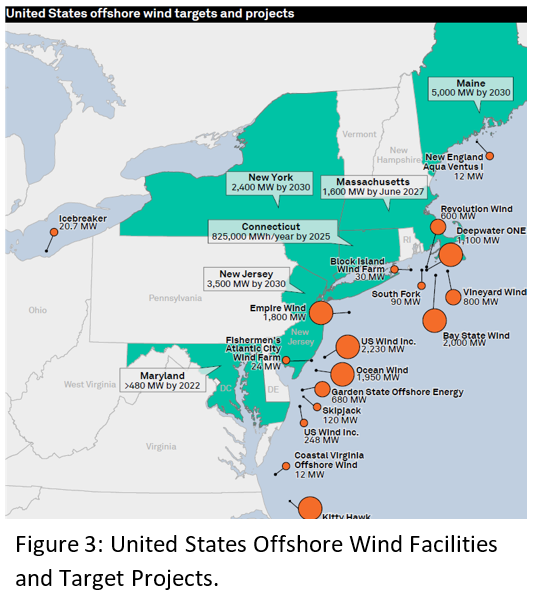

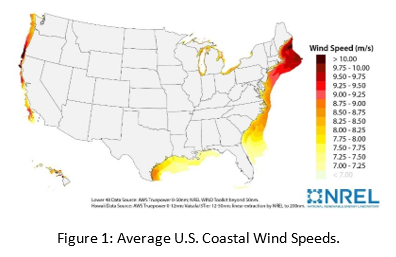

Although the United Kingdom, Germany, China, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark are the current world leaders in both the number of wind turbines on-line and megawatt capacity, the U.S. is moving forward. Data on the technical resource potential suggest more than 2,000 gigawatts (GW) could be accessed in state and federal waters along the maritime coasts of the United States and the Great Lakes.2

Here are some current offshore wind projects in the U.S.:

- Rhode Island is the home of the first energy-producing U.S wind farm, the 30-megawatt (MW) Block Island development located in state waters;

- Virginia installed the first offshore wind turbines in federal waters with the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind 12 MW pilot project which is almost ready to enter commercial service;

- An 800 MW project off North Carolina has been planned;

- The Vineyard 800 MW wind farm off Massachusetts is undergoing federal review;

- New York is aiming for an installed wind capacity of nine GWs by 2035; and

- Maryland is planning for a wind energy farm consisting of 32 turbines to come on-line in 2023.

A summary of the status of activity in the different states can be found at https://www.boem.gov/renewable-energy/state-activities. See Figure 3.

Who Guides the Regulatory Process?

Federal laws are the principal legal vehicle governing the development of U.S. offshore wind energy generation, with state and local laws coming into play if the facility is located in state waters. The U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) directs all renewable energy projects on the Outer Continental Shelf, including the administering of leases.

Pursuant to the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (42 USC §13201 et seq.) BOEM is required to coordinate with relevant federal agencies and affected state and local governments, obtain fair returns for leases and grants issued, and ensure that renewable energy development takes place in a safe and environmentally responsible manner.3

Other relevant legislation that may impact BOEM’s project facilitation, lease approval and oversight includes the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA); Endangered Species Act (ESA); Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA); Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA); Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (The Jones Act); and Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCLSA). Other federal agencies such as the U.S. Coast Guard, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers may work with BOEM to regulate certain activities and/or the impacts of offshore wind energy projects on specific coastal and marine resources.

How Does BOEM’s Regulatory Process Work?

BOEM’s renewable energy program occurs in four distinct phases: planning and analysis; leasing; site assessment; and construction and operations.4

1. Planning and Analysis (1-2 years)

The planning and analysis phase seeks to identify suitable areas for wind energy leasing consideration through collaborative, consultative, and analytical processes that engage stakeholders, tribes, and state and federal government agencies. This is the phase when BOEM conducts environmental compliance reviews and consults with tribes, states, and natural resource agencies.

2. Leasing (1-2 years)

Commercial wind energy leases may be issued either through a competitive or noncompetitive process. A commercial lease does not grant the right to construct any facilities but offers the ability to develop specific plans which must be approved by BOEM.

3. Site Assessment (up to 5 years)

The site assessment phase includes the submission of a site assessment plan, which contains the lessee’s detailed proposal for construction. BOEM may approve, approve with modification, or disapprove a lessee’s site assessment plan.

4. Construction and Operations (2 years)

The construction and operations phase consists of the submission of a detailed construction and operations plan. BOEM conducts environmental and technical reviews (under NEPA) of the construction and operations plan and decides whether to approve, approve with modification, or disapprove the plan. If approved, the company will enter a 25-year commercial lease, with the possibility of renewal beyond the initial period.

How Can Scout Assist You?

Developing a wind energy site may be a time-consuming process, and developers face several hurdles to get to the finish line. Although the cost may be prohibitive to some, future cost reductions could occur through engineering innovations, industrialization, a favorable political climate, and market competition. With our staff of experienced scientists, Scout is ready to help guide you through the complex regulatory process or guide you to understand how these projects might impact your military mission. For further inquiries or more information please contact hello@scoutenv.com.

1Advantages and Challenges of Wind Energy, Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, 2016.

2Computing America’s Offshore Wind Energy Potential, Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, 2016.

3Renewable Energy: Regulatory Framework and Guidelines, BOEM, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C., 2021.

4See generally BOEM Fact Sheet, Wind Energy Commercial Leasing Process, BOEM, Washington, D.C., January 24, 2017.