All it takes is a Google image search for “San Diego Waterfront” or a landing at Lindbergh Field to appreciate the fact that San Diego Bay is the defining feature of America’s Finest City.

A Century of Dredging and Filling has Shaped the San Diego Bay We Know Today

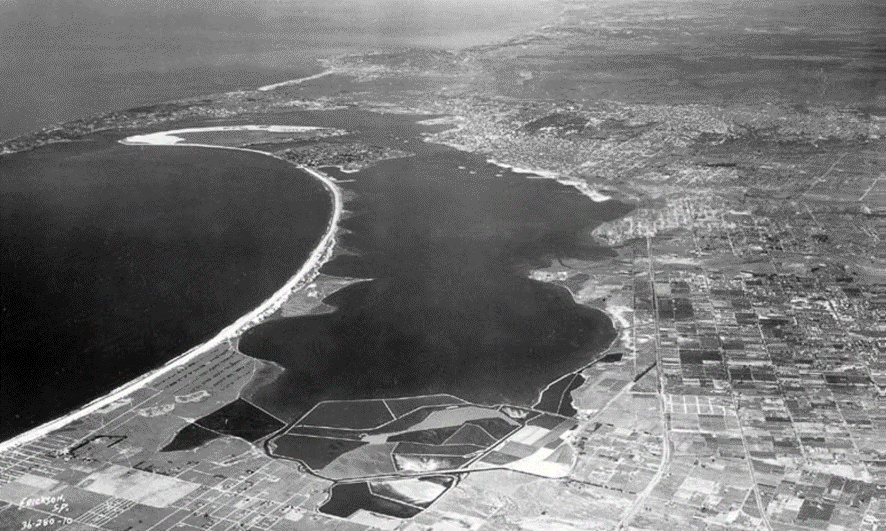

San Diego Bay is unique – it was formed naturally, and, even in the 1800s (before major dredging activities were undertaken), had a navigation channel that was deep enough to allow large sailing vessels to enter the bay. Since this time, much of the bay’s waterfront and navigable maritime areas have been significantly modified by historic dredge and fill projects. Navigational channels have been added, deepened, and maintained to accommodate large military and commercial ships. Dredge and fill projects have added land for port facilities, airport operations, commercial activities, and military uses. In addition, dredged material has been used beneficially for habitat creation (such as eelgrass beds and mudflats) and has been used to create barriers as part of coastal resiliency efforts.

The development of Coronado Island is a great example of how dredging has shaped San Diego. In 1888, the Hotel Del Coronado was built on what was described as a “poorly developed sand spit.” The spit consisted of two large sand bars or “Islands” (north and south) separated by a small stretch of water known as the “Spanish Bight.” The island grew in popularity and, despite the construction of a stone seawall, remained relatively unchanged. In 1917, Naval Air Station (NAS) San Diego was commissioned, and by the end of WWII, Navy dredge projects had expanded and developed North Island into a runway; filled the “Spanish Bight” which connected the two islands thus creating what we know today as Naval Air Station North Island; and added land to the South Island to fortify the Silver Strand and construct the Naval Amphibious Base Coronado, which was commissioned in 1944.

1943 Filling of Spanish Bight at NAS North Island. Courtesy of the San Diego History Center.

Large land reclamation projects like those that built Coronado Island, Shelter Island, Harbor Island, Lindbergh Field, and much of the rest of the bayfront are responsible for the San Diego Bay we know today. Currently, large projects that significantly alter the waterfront are unlikely to be pursued due to permitting complexities and the lack of local mitigation opportunities. This does not mean dredging in San Diego Bay has stopped. Modern dredging projects in San Diego Bay and across the nation primarily deal with maintenance dredging activities of channels and berthing areas, capital improvement dredging when new types of vessels require deep drafts that the bay currently offers (such as the safe navigation and berthing of modern NIMITZ-class nuclear-powered aircraft carriers at NAS North Island), and for beneficial reuse projects such as habitat restoration and beach nourishment. There have also been a number of sediment cleanup dredging projects conducted in the bay (e.g., the Shipyard Sediment Cleanup Project, NTC Boat Channel dredging) whereby contaminated sediments from legacy industrial sites are removed from the bay bottom and placed in a permitted landfill.

Current Dredging Practices

Unlike the dredging done in the early to mid-part of the 20th century, the dredging projects of today are subject to myriad federal, state, and local regulations that ensure projects do not negatively impact

Best Management Practices

So where has all this permitting landed us? Modern dredge projects are performed in the least impactful way and follow best management practices and utilize standardized dredge methodologies and technologies in order to protect the water quality, aquatic ecosystems, public health and sites of cultural historical and/or tribal significance. Dredging sites and depth are predetermined and modern dredging equipment and navigational technologies ensure the removal of material is clean, precise, and channels are structured according to strict standards.

Material Management

Once the material is removed, it must go somewhere. The characteristics and quality of the dredged material often dictate the manner of its disposal or potential reuse. Dredged material deemed

Mitigation/Habitat Restoration

Today dredge projects that impact aquatic ecosystems are often required to provide mitigation in order to offset the local environmental impacts. Mitigation sites must reflect the ecosystem damaged from the associated project. The beneficial reuse of otherwise wasted dredge material is one of the most efficient and impactful ways a dredge project can offer mitigation. Dredging and habitat creation often go hand-in-hand because clean bay sediments of the appropriate grain size are needed to build habitats. The lack of suitable materials is often a limiting factor in creating or enhancing mitigation/habitat restoration sites.

Scout, along with their partner firm Merkel & Associates, recently prepared an environmental assessment (EA) for the establishment of eelgrass habitat in San Diego Bay. Since its celebrated establishment in 2008, the Navy has used credits from the Navy Region Southwest San Diego Bay

Eelgrass Mitigation Bank (Bank) to offset unavoidable eelgrass and other habitat impacts from infrastructure projects and testing and training activities in San Diego Bay. As analyzed in the EA, the Navy proposes to add to the existing Bank by expanding eelgrass habitat at one or more sites through the placement of suitable dredge material.

Conclusion

Historic dredge and fill activities have shaped the current shoreline of San Diego Bay. The millions upon millions of cubic yards of bay dredge and fill have created land for military bases, shipping terminals and an airport, shipyards, hotels and commercial operations, recreation opportunities and parks, and habitat restoration. In addition to shoreline fill, historic and ongoing dredging operations ensure that the bay’s channels, approaches, piers, and wharves have adequate depth for safe navigation and berthing of military, commercial, and recreational vessels. This is particularly important for the Navy so that they can always meet their mission requirements and national security concerns. Dredging is also an important way in which legacy contaminants are removed from the bay, thus enhancing the aquatic environment.

Until the end of the 20th century, large scale bay dredge and fill projects were performed with minimal assessment of potential environmental impacts and mitigation requirements. Today, modern dredge and fill practices are highly regulated and often require mitigation. Regulations ensure the protection of local water quality, aquatic ecosystems, and public health, and mitigation offsets unavoidable impacts. Environmental dredging projects like habitat restoration and beach/marsh nourishment help protect San Diego’s environment and infrastructure. It is important that future dredging projects are mindful of the ecosystems they can both destroy and create.

Scout is uniquely qualified and poised to handle a variety of dredge permitting and aquatic science services. These services and more are better described in this previous Scout Blog by Senior Aquatic Scientist Barry Snyder. Contact us today for help with your next aquatic or dredging project at hello@scoutenv.com.